X-ray and Rotational Luminosity Correlation and Magnetic Heating of Radio Pulsars - Notes on Shibata et al. 2016

X-ray and Rotational Luminosity Correlations - Summary

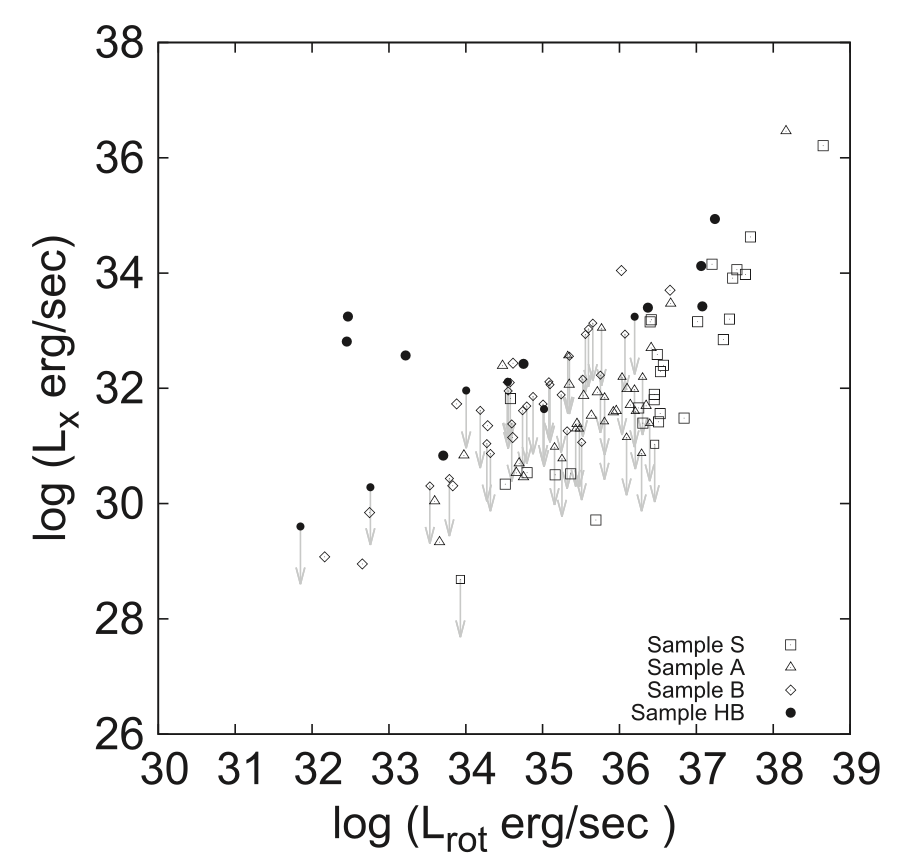

The paper “X-ray and Rotational Luminosity Correlation and Magnetic Heating of Radio Pulsars” studies the correlation between X-ray luminosity \(L_X\) and rotational luminosity \(L_\text{rot}\) of radio pulsars. Until now, all fits to this relation have been statistically unacceptable. Using Monte Carlo simulations, which take into account effects that might obscure the relation, this paper obtains a statistically acceptable relation. They also find that pulsars with unusually high X-ray luminosities are either soft gamma-ray pulsars or pulsars that are thermally bright compared to the standard cooling curve. On the other hand, low X-ray luminosities have been found in pulsars with a dim pulsar wind nebula.

Context

Why do we want to know the relationship between high-energy luminosity and rotational luminosity? Essentially, by constraining it we can get an idea of the emission and particle acceleration mechanisms of the pulsar magnetosphere. The rotational luminosity depends on the pulse period and its derivative, and is therefore easy to calculate. The gamma-ray luminosity follows \(L_\gamma \propto L_\text{rot}^{1/2}\) for young pulsars, but the X-ray luminosity shows a steeper correlation, about \(L_X \sim 10^{-3}L_\text{rot}\). The gamma-ray relation implies a primary origin, and the steeper curve could imply secondary pairs. To be honest, I’m not sure what this means. But several papers have observed these kinds of trends, all of them suggesting correlations with linear regression.

This paper aims to take into account the effects that can distort the relationship, and then use a Monte Carlo simulator to compare the simulated distribution with the observed data. They hope to find a statistically acceptable “hidden” relationship between the two luminosities. One reason why the relation could be contaminated is the influence of different types of sources, such as magnetars (anomalous X-ray pulsars and soft gamma-ray repeaters), central compact objects and X-ray isolated neutron stars. All of these show excess X-ray luminosity.

- Magnetars: Some of their main properties are

- persistent X-ray luminosity (\(10^{33}-10^{36}\)erg/s), greater than \(L_\text{rot}\),

- high time variability, and

- large breaking torque, implying \(B_d \sim 10^{14--15}\)G.

- Central Compact Objects are bright X-ray sources located near the centres of supernova remnants with

- small magnetic field, \(B_d \sim 10^{10}\)G, and

- no radio emission.

So the sample of pulsars in this study consists of objects with known period, period derivative, distance, observed in radio, no magnetar, no millisecond pulsar, and not in a binary system.

How did they do their analysis?

The data set for each pulsar should include the X-ray and rotational luminosities as well as the distances. They then use a Monte Carlo simulator to generate a large number of simulated values for the X-ray luminosity and then construct a probability density function. This simulator takes into account possible effects that cause scatter in the plot of the luminosity relation. There are four steps they include in their simulation:

- Include geometrical effects (such as aniostropic radiation, with randomly oriented viewing angles).

- Add some X-ray luminosity (from the dissipation of the crustal magnetic field).

- Take into account the uncertainties in the estimated distance and interstellar absorption.

- Consider the observable flux limit (mainly determined by the instrument).

The simulation is then repeated \(N\) times, where \(N\) is usually \(2\times 10^4\) for each pulsar.

So what is the result?

They find a best fit model relationship of \(L_X = 10^{-4.75}L_\text{rot}^{1.03}\). To obtain this distribution, \(\sigma \sim 0.7\) and \(F_\text{lim} \sim 10^{-14}\)erg/cm\(^2\)/s. Then only \(n\) can be free and the best result is found for \(n \sim 2\), which is an anisotropy with \(F_X \propto \cos^2 \theta\). This is only true without the high-magnetic-field pulsars (\(10^{13}\)G), because this sample does not seem to show any correlation in the luminosities. The excess X-rays probably come from the magnetic field decay. They then identify the pulsars with large X-ray efficiencies, which are soft gamma-ray type and thermally bright pulsars.

Finally, they come to the standard conclusion that further analysis with much better quality data, which could be separated into thermal, magnetospheric, and pulsar wind nebula components, may give a more precise discrimination of the individual sources of emission, and thus contain the clues to find the hitherto unknown physics controlling the X-ray efficiencies.

And that could be an interesting project…